The paradoxical queer history of Iran

This past February, something special happened.

For the first time in the 44-year history of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the majority of trade unions and notable social activists inside the country published a charter that demanded basic rights that, in their words, need to be addressed immediately. One of their demands was “The immediate and unquestionable removal of all forms of the discriminatory structure against sexual minorities and people with gender-nonconforming identities. Recognizing LGBTQAI+ rights and decriminalizing them.”

A country that often vilifies, or at best ignores, the LGBTQ+ community now boldly included their rights in this important charter. LGBTQ+ rights are more often being brought up by right-leaning oppositional groups outside of the country as well.

The attitude towards the community is clearly shifting on a structural level, even within the government.

So what brought us here?

A queer paradise

Tehran, the capital city of Iran, was once described in the 70s by Jerry Zarit (an American professor who used to teach in Tehran) as a sexual paradise, one that provided him with the most exciting time of his life in which he wasn’t constrained by Western restrictions and homophobia.

In the 1970s, the American press was very enthusiastic about Tehran’s robust gay culture. At that time, Iran was considered to be one of the friendlier places when it came to non-conforming sexual and gender expressions.

Going back even further, same-sex relationships were once not only tolerated but embraced in Iranian society.

Before the late Qajar era and the first revolution in 1906, Iran had an extremely robust culture of accepting and romanticizing concepts that today would be categorized under the LGBTQ+ flag.

This is clearly reflected in the country’s rich literature, especially its poetry. Even under the current reign of the highly anti-LGBTQ+ Islamic Republic, Iranian students learn Persian poetry and literature that is filled with male homoeroticism. To fully censor this phenomenon is to censor almost the whole of Persian poetry. Therefore, it’s impossible to deny this fact, even for Iran’s modern homophobic superstructure.

The story of Sultan Mahmoud Ghaznavi and his lover, Malik Ayaz, is one of the most popular stories in Iran about a same-sex relationship. It has been remembered fondly by Iranian society for more than a thousand years. Of course, a lot of such relationships have been whitewashed in recent years through revisionist attempts to create the illusion that all these male lovers, such as the beloved Shams and Rumi, were in fact, “good friends.” This is frustratingly similar to what has happened to much of pre-Christianity Western literature, such as changing the nature of Achilles and Patroclous’ relationship.

It is, however, important to realize that before Europeans ever came to Persia, same-sex relationships in Iran weren’t the same as homosexuality. While we may identify them as part of the LGBTQ+ umbrella, we also need to recognize that we are redefining a historical phenomenon within the boundaries of a modern concept.

Much like in ancient Greece, same-sex relationships in Iran at times included unequal relations. For example, even though the story of Sultan Mahmoud and Malik Ayaz is of great significance and literary beauty, Ayaz is Sultan Mahmoud’s slave and the relationship is pederastic in nature – an adult man of higher status falling in love with a young boy of lower status.

This trend of pederastic relationships was looked down upon by the modern educated intelligentsia in the 1900s. They concluded that pederastic relations, and sometimes same-sex relationships in general, were the result of meticulous sex segregation in the country. In their belief, because women and men used to live predominantly apart from one another, the culture of homoeroticism flourished. Influenced heavily by the Western conception of gender norms and relationships, they intended to dismantle this subculture to pave the way for a Westernized Persia.

This criticism from the intelligentsia was not the only one that targeted same-sex relations. Affected by colonialism, Islamic fundamentalism as a reaction called for a literary interpretation of the Koran and a much stricter implementation of Sharia Law.

At odds with one another on a fundamental level, the intelligentsia and the fundamentalists nevertheless found a common enemy.

Paradise lost

During the Pahlavi era, under the reign of Riza Shah, Persia was industrialized and modernized. The name was officially changed to Iran as a result of geopolitical maneuvers.

This marked an interesting time for the LGBTQ+ community. Nationalists and intellectuals saw same-sex relations and gender nonconformity as alien concepts that were introduced to Iran through foreign and “less advanced” people, such as Greeks, Turks, and Arabs. Due to the lack of documents about homosexuality during pre-Islamic Persia, they propagated the idea that this culture was an innovation that took place in Islamized Persia and we, as true heirs of the Persians of the past, must not tolerate it.

As a result, love for the opposite sex was celebrated heavily and was seen as a brave act that put it in sharp contrast with the expression of homoerotic love.

Sadegh Hedayat, the most renowned Iranian novelist of all time, didn’t express his homosexuality openly even though he condemned many social norms regularly, such as Islam as a whole. Because not only was homosexuality seen as a sin by the emergent fundamentalists, but it was also seen as an anti-progressive act of backwardness that belonged to the past.

But of course, the structural elimination of same-sex relationships across Iran didn’t truly eliminate LGBTQ+ people. Rather, it created a different, more oppressive atmosphere as Iranians entered the 20th century.

Corruption, corruption

The extent to which Riza Shah personally supported gay rights is unclear, but his anglophilia as well as his overall fascination with the West paved the way to create a more relaxed environment for LGBTQ+ people inside his court.

In February 1978, approximately one year before the Iranian Revolution and eighteen years before the signing of the Defense of Marriage Act in the United States, two gay men had a secret wedding and were officially married in Tehran.

One of the grooms was Bijan Saffari, a famous architect who was responsible for Daneshjoo park, a widely popular park in Tehran for the LGBTQ+ community. It had subtle homoerotic sculptures that are still displayed in the park.

Saffari was the son of a high-ranking senator in Shah’s senate, and his boyfriend was the son of one of the wealthiest men in Iran. For obvious reasons, the marriage was only open to the people associated with the late king, Muhammad Riza Shah. The queen, Farrah Diba sent out a congratulatory message, and so did many well-known celebrities, such as the Oscar-nominated Shohreh Aghdashlou.

Unsurprisingly, this luxurious and magnificent marriage in one of the most expensive hotels in the country attracted a lot of unwanted attention.

Saffari and his husband went to great lengths to make sure this marriage stayed a secret. Nonetheless, words got out and it brought fury from all sides.

The Tudeh Party’s banned newspaper, which was run by the pro-Soviet Communists, called the act “dirty.” At that time, the intellectual sphere of the country was mostly influenced by Marxist-Leninist ideas that deemed homosexuality an imperialist construct that the Shah was enforcing inside the country.

The fact that a few people who were associated with the royal family were gay – such as the queen’s dress designer, Keyvan Khosravani – created the image, propagated by the opposition, that the Shah was importing capitalistic cultures from the West, at the peak of which stood the unholy act of sodomy.

This belief was intensified when American socialites who were given special immunity and rights in Iran (the capitulation law), spent their days in the Rasht29 club and other luxurious places throughout the country that were known both for their bourgeoisie aesthetics as well as openness to LGBTQ+ expressions.

This phenomenon was well-represented in the writings of Americans and the press at the time. Tehran was known to be a sexual paradise, specifically for rich gay Americans.

The hatred for all things American – including anything outside of heteronormative relationships – was popular among multiple political movements, both secular and religious, which represented both the earlier intellectual/socialist understanding of mankind’s natural state of being and the Fundamentalist interpretation of Islam.

This coalition of the right and the left put the LGBTQ+ community in a strange and unpleasant position during and after the 1979 revolution.

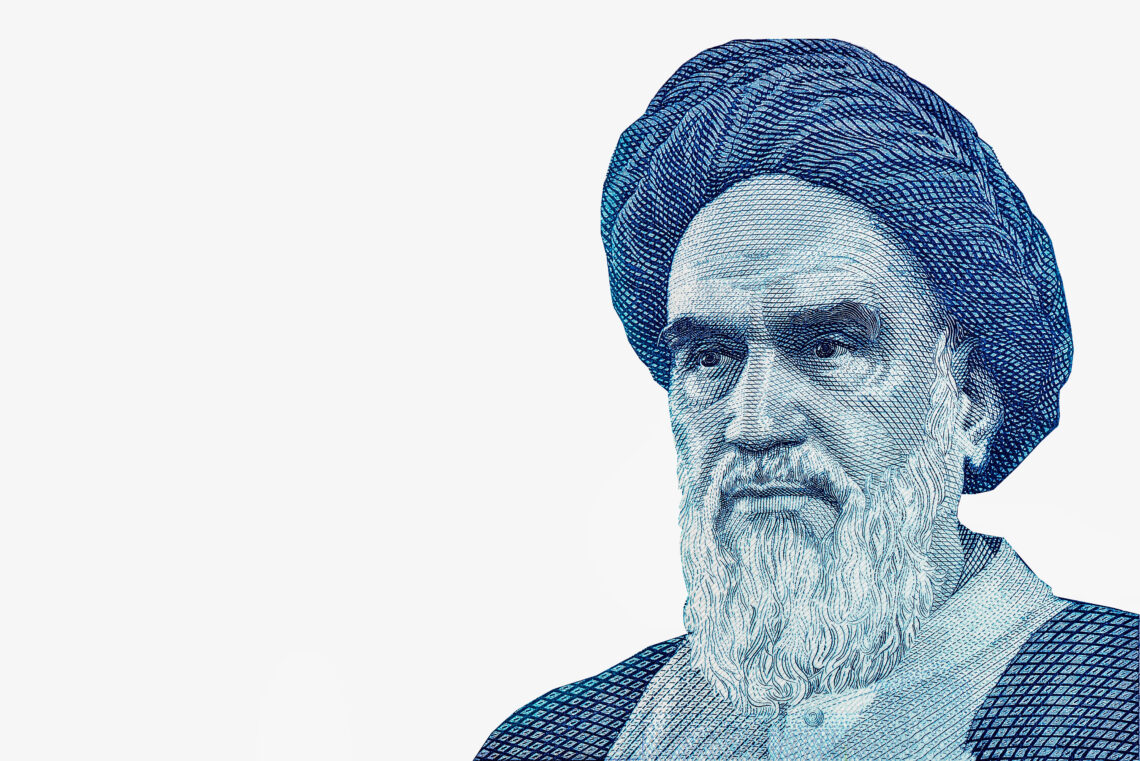

When the renowned journalist Oriana Fallaci asked Ayatollah Khomeini after the revolution about his opinion on homosexuality, he responded, “I know there are societies where men are permitted to give themselves to satisfy other men’s desires. But the society that we want to build does not permit such things. In Islam, we want to implement a policy to purify society, and in order to achieve this aim we must punish those who bring evil to our youth. Don’t you do the same? When a thief is a thief, don’t you throw him in jail? In many countries, don’t you even execute murderers? Don’t you use that system because, if they were to remain free and alive, they would contaminate others and spread.”

He finished his take on the matter by saying, “Corruption, corruption. We have to eliminate corruption.”

The return to homosocial spaces

As a result of Iran’s modernization since the end of the Qajar Dynasty, the segregation of genders had slowly faded away and same-sex environments gave way to coed spaces in which Westernized heteronormative socialization was encouraged.

However, Khomeini’s hatred for gay people was only rivaled by his detestation for irreligious mingling between men and women, which led to the complete dismantling of mixed-sex spaces in the 1980s and the return to old-fashioned same-sex environments.

“History repeats itself, first as a tragedy, second as a farce,” Karl Marx once said. While far from a farce, one cannot help but chuckle a bit about the rise of homoeroticism and homosexual subcultures in Khomeini’s Iran after 1979.

Minoo Moallem, a scholar of gender studies, said, “The convergence of popular culture practices grounded in Shia mythology, modern nationalism and pre-modern and modern views of gender and sexuality creates a homosocial and homoerotic world for warrior men to establish a community of brothers who recognize themselves through the concomitant process of othering and domesticating women.”

Similar to how pre-modern Iran cultivated a subculture of same-sex relationships due to the segregated nature of society, modern Iran went down the same path. This was exacerbated by the Iran-Iraq war, which intensified the ideals of brotherhood and homosociality.

A society of contradictions

In recent years, things have changed drastically. There have been crackdowns on Daneshjoo Park, which in the past has been ignored by authorities. In addition, the president, himself, Ebrahim Raisi, made an unapologetic speech in which he condemned homosexuality as the source of all evil right after the imprisonment of two LGBTQ+ activists.

This seems to be a response to modern LGBTQ+ expressions that do not fit well within the Islamic tolerance for a very specific form of homoerotic/homosocial behavior due to the segregation of genders.

It is hard to say why or how the LGBTQ+ movement has gained more visibility and support in recent years. But undeniably, the new social superstructure and the influence of the internet have fostered the conditions for LGBTQ+ people to become more visible and confident in expressing themselves outside of the Islamic Republic’s heteronormative standards.

The contradictions inside the system are bringing it down on a high level, which, hopefully, will lead to the freedom of LGBTQ+ people and a more tolerant society.

source https://www.lgbtqnation.com/2023/05/the-paradoxical-queer-history-of-iran/

Comments

Post a Comment